-

Eamon Ore-Giron

Gauri Gill & Rajesh Vangad

Yun-Fei Ji

Tuan Andrew Nguyen

Firelei Báez

Weave the Future Golden draws its title from an essay by Sophia Al-Maria, Weave the Future Golden over Dark Days, a poetic call to action. She writes, "Use the tools you are given. Confront your histories with honesty. Rescue the unknowable future."¹

Weave the Future Golden highlights a group of artists who summon their ancestral past in order to imagine alternative futures. Tapping into both personal and collective histories, each artist reinterprets folkloric traditions as repositories of shifting cultural knowledge. Folklore, commonly understood as traditional knowledge passed from generation to generation, has been historically undermined by colonial and imperial powers. Looking to folklore as sites of memory to be transformed, these artists reshape traditional culture into new narratives. The resulting artworks stir up conversations that reflect contemporary societal undercurrents in an attempt to evoke our collective subconscious.

-

Eamon Ore-Giron

-

In his abstract geometric paintings, Eamon Ore-Giron combines motifs and symbols drawn from sources that span geographies and time: the stylized geometry of Incan jewelry, Brazilian Neo-Concretism, Italian Futurism, and the spatial arrangements of Russian Suprematism. Inserting pictorial and rhythmic structures from the Global South into an expanded history of transnational abstraction, Ore-Giron's works embody what curator Marcela Guerrero refers to as “the sound and color of mestizo synesthesia.” His richly colored compositions draw on vocabularies of architecture, textiles, maps, hieroglyphics, and astral charts to arrive at an iconography that is uniquely his own. Bringing the past into dialogue with the contemporary, his practice seeks to destabilize linear, European art-historical inheritances by suggesting a shared heritage of forms and ideas.

-

EAMON ORE-GIRON, Infinite Regress CXL, 2020 (detail)

EAMON ORE-GIRON, Infinite Regress CXL, 2020 (detail) -

GAURI GILL & RAJESH VANGAD

-

Over the last decade, Gauri Gill has developed collaborative partnerships in an effort to blur the line between photographer and subject. In this instance, Gauri Gill and renowned Warli painter, Rajesh Vangad worked together on Fields of Sight, a series of photographs taken by Gill and then hand-inscribed in black paint by Vangad to co-create new imagery of life in Ganjad, a small farming village. These fantastical works combine the contemporary language of photography with that of ancient Warli drawing, a genre of folk art which utilizes the geometric vocabulary of circles, triangles, and squares to symbolize different elements in nature, and the world. In Three Suns, radial forms emanate from three statuesque male figures and Vangad himself is pictured on the far left. Upon closer inspection, each ray consists of miniature geometric figures representing people and animals, partaking in daily life as hand-drawn trains and planes whiz through the landscape. Fields of Sight address the challenges faced by indigenous communities, whose land rights are under threat as their environment changes and natural resources are either depleted or totally exhausted as modernity vies with rural life.

-

GAURI GILL and RAJESH VANGAD, Three Suns from the series Fields of Sight, 2019 (detail)

GAURI GILL and RAJESH VANGAD, Three Suns from the series Fields of Sight, 2019 (detail) -

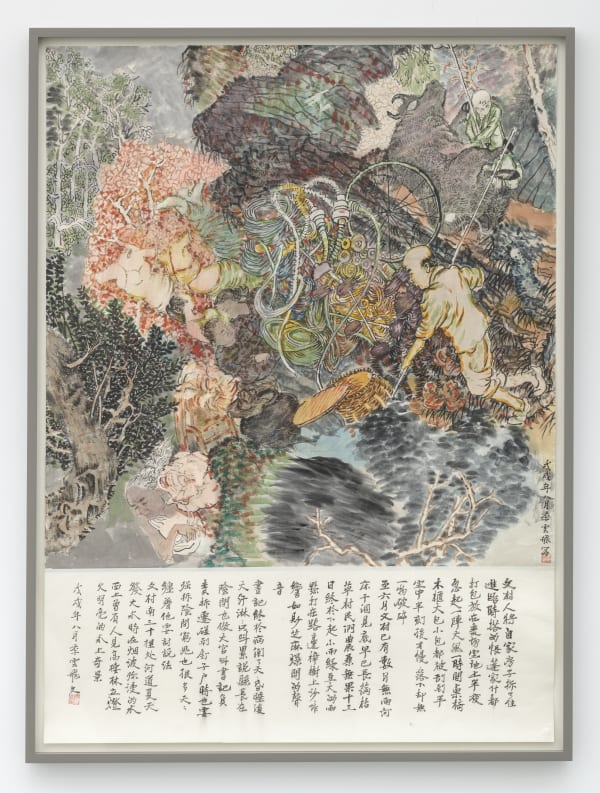

Yun-Fei Ji

-

Yun-Fei Ji utilizes the structures and symbols of folkloric tradition to speak truth to power. Full of phantoms, demons, and other spectral characters, Ji’s paintings have frequently functioned as metaphorical critiques of oppressive power structures—and strategies of defiance. In his ink and watercolor compositions, these ghostly figures are stand-ins for the complex political undercurrents and cultural tug-of-war shaping rural communities in a rapidly developing world.

Ji is inspired by the ghost stories that he first learned growing up in the countryside during the late Chinese Cultural Revolution. He employs the stacked perspective and flattened space of classical Chinese painting to tell contemporary stories that, while geographically specific, speak to a collective human experience. The work often comments on the political realities of both the US and China, expressed in codes by using metaphor and allusion. There is a satirical streak, and his love of the grotesque is balanced with humor and a deep sense of irony. Each work is an act of resistance, insisting that narratives of displacement and environmental destruction are worth preserving.

-

-

Tuan Andrew Nguyen

-

Tuan Andrew Nguyen explores the power of storytelling through video, sculpture and photography. Situated at the intersection of politics and history, Nguyen employs Vietnam's spiritual culture and tumultuous past as grounding forces to navigate global systems of power. Nguyen extracts and re-works dominant, oftentimes colonial histories and supernaturalisms into vividly imaginative vignettes.

Spirit of Bidong is a photographic work that depicts an imagined ‘last man on earth.’ Created in conjunction with Nguyen’s video project The Island, a film shot on Pulau Bidong, an island off the coast of Malaysia that became the largest and longest-operating refugee camp after the Vietnam War. The artist and his family were some of the 250,000 people who inhabited the tiny island between 1978 and 1991. The film takes place in a dystopian future, the island now overgrown by jungle and filled with crumbling monuments and relics.

-

TUAN ANDREW NGUYEN, Bidong 1, Bidong 2, Bidong 3, 2017

-

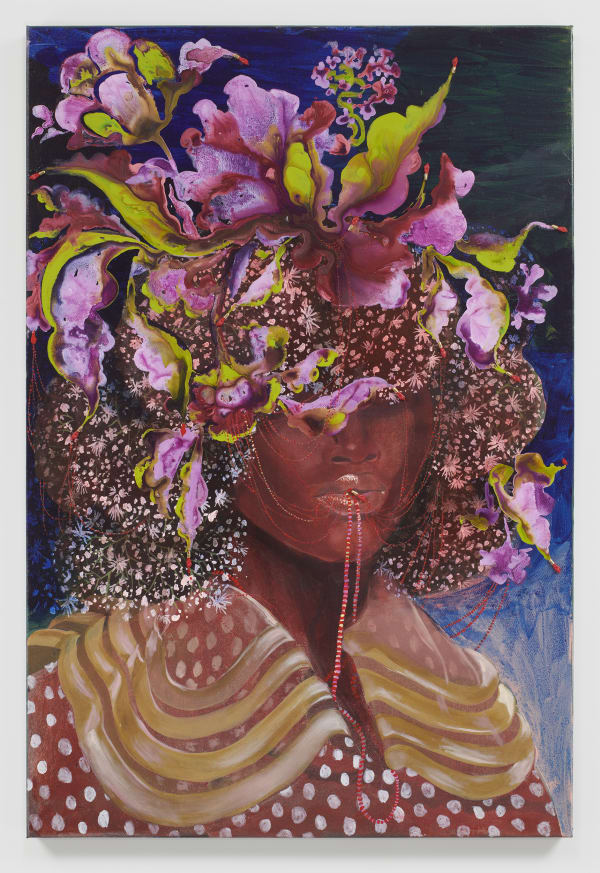

Firelei Báez

-

Firelei Báez casts diasporic histories into an imaginative realm, re-working visual references drawn from the past to explore new possibilities for the future. Drawing visual cues from folklore, sci-fi, and fantasy, her paintings frequently portray change-making creatures that inhabit fictional alternate universes with a stance of self-determination. Central to this work is the feminine-archetypal ciguapa, a trickster from Dominican folklore who, for Báez, embodies the potential to defy oppressive convention and break through generations of karmic loads. Shown here with lustrous manipulated hair, the figure serves as a shape-shifting agent for change—crouching in a strikingly active and self-reliant posture, the character becomes “so possessed of her body that she can easily, acrobatically, move between spaces.”

-

FIRELEI BÁEZ, Untitled, 2020 (detail)

FIRELEI BÁEZ, Untitled, 2020 (detail) -

Báez's paintings frequently portrays female Afro-Caribbean figures sidelined by—and yet absolutely foundational to—Western historical macro-narratives. This portrait depicts the diasporic goddess-figure known as Maman Brigitte in Haitian vodou and as Oya within the Yoruba tradition. In Haitian lore, she was a catalytic force behind the onset of the Haitian Revolution, credited with inspiring priestesses to sound the drums that led troops of enslaved people forward to fight for their freedom. By depicting the deity in a manner that layers symbolic references to subaltern revolutionary histories and Western portraiture, Báez encourages a more complex view of the independence movements that occurred throughout the Americas during this period. From Maman Brigitte’s mouth hangs an azabache, a symbol of protection in Latin America and the Caribbean, carving out space within the art historical canon for healing inasmuch as resistance.

-

____________________________________________________________________________

¹ Sophia Al-Maria, Sad Sack: Collected Writing, London, United Kingdom: Book Works, 2019.

² Gauri Gill, excerpted from Gauri Gill, Fields of Sight, exhibition text, Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata, West Bengal 2014

³ Video Feature for James Cohan Viewing Room, Firelei Báez, produced by James Cohan, 2020.

Weave the Future Golden: Online Viewing Room

Past viewing_room