-

-

Elsa Gramcko (b.1925, Puerto Cabello, Venezuela, d.1994, Caracas, Venezuela), blended geometric abstraction and surrealism to produce visually arresting paintings, dimensional assemblages and totemic objects. Gramcko earned a distinct place in the history of Latin American art, thanks to her independent drive and her refusal to subscribe to one modality of art production. Her art practice spoke critically of the shifting social and economic landscape of Venezuela at the height of the country’s prosperity in the 1950s and 60s. She repurposed industrial debris and automobile parts– symbols emblematic of the country’s booming oil extraction economy. By reclaiming things, Gramcko imbued them with a sense of poetry and humanism as a silent protest to Venezuela's rampant modernization.

Elsa Gramcko: The Invisible Plot of Things, curated by Gabriela Rangel, is presented in partnership with Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino in Houston, Texas and with the collaboration of Luis Felipe Farías. This exhibition of over forty artworks spanning three decades, from the 1950s through 1970s, attest to Gramcko’s significant contributions to global modernism, marked by her distinctive language of abstraction. -

-

In 1954, Gramcko attended studio art classes at the School of Plastic and Applied Arts of Caracas conducted by the Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero, a pioneer of geometric abstraction and the driving force of Los Disidentes. Gramcko developed a medium-sized series of oil paintings on canvas constructed with hard lines, irregular machine-like shapes, and flat background colors. The rare paintings from this period demonstrate her efforts to reconcile expression with geometry.

Her dynamic palette evolved into larger canvases of tubular shapes composed using complementary hues on flat monochromatic backgrounds. By the end of the 1950s, she developed a new body of work characterized by elegant, biomorphic shapes with a strong graphic inflection that positioned her as a singular artist among her peers.

-

Elsa Gramcko at her solo show and alongside critic José Gómez-Sicre with painting Nº 6 at the Pan American Union, in Washington D.C., 1959.

-

The arrival of Informalism [a gestural and improvisatory methodology of artmaking] to Venezuela in 1959 also coincided with the artists Jesús Rafael Soto’s and Alejandro Otero’s brief explorations of assemblage and collage as reworked by French Nouveau réalisme. Both Soto and Otero lived in Paris, but traveled often to Caracas.

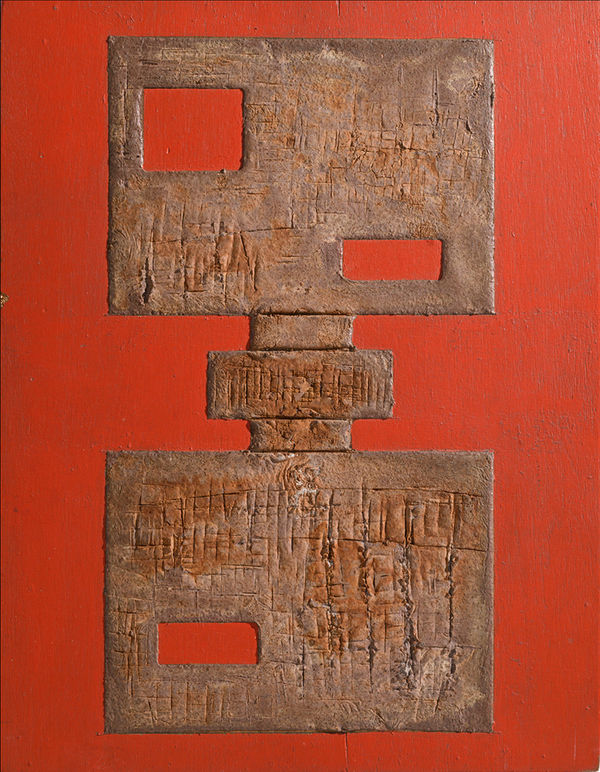

Even though Gramcko did not consider herself part of the Informalist group, her works were a reference for local practitioners of the tendency. In the 1960s, Gramcko abandoned oil painting to explore the thickness and density of materials. She began a series of paintings (R) in which she challenged traditional artistic methodologies for the use of an array of industrial materials such as sand, pigments, and glues to produce barren textures with a tactile quality, resembling lunar landscapes, signaling a shift in her aesthetic center of gravity toward assemblage.

-

"For me, texture is a distraction. Intricate surfaces tend to lead to the path of intuition and form, which is what matters.” - Elsa Gramcko

-

-

In the early-to-mid 1960s, Elsa Gramcko embraced gritty textures, rusted metals and car parts, working against the illusory optimism of the Kinetic movement championed by her Venezuelan contemporaries. She recomposed these cast-off materials of modernity as a meditation on a country ruled by oil. Her art practice was a critical approach to what Rangel and art historian Aruna D’Souza describe as “petro-modernity”; a period of booming oil-extraction in Venezuela, coupled with rapid urban development in the capital city of Caracas in the 1960s and 70s.

Gramcko’s usage of glue, paint, acids, and other elements generated heavily textured and coarse surfaces suggestive of the type of corrosion that results from the passage of time. When she used a fastener, a lock, a wheel, or cells torn from a car battery, she created a new context for the object. The placement of embedded objects was intentional, and she often directed energy toward the center of her pieces. The title of the works, in turn, referenced ancient tectonics or architectural elements, such as castles, walls, or towers.

-

-

Elsa Gramcko in front of her assemblage, 1966.

Elsa Gramcko in front of her assemblage, 1966. -

“If the automobile was the emblem and the means of traversing a petro-city plagued by highways, devolving into chaos, where a practically non-existent public transport system could not meet the needs of new residential and commercial developments, then the assemblages of things that Gramcko collected provide a symbolic compendium of the static and fossilized waste from this urban instrument of transport and circulation that had made Caracas—alongside Mexico City and Sao Paulo—the twentieth century’s South American center of accelerated progress and consumption.” - Gabriela Rangel

-

-

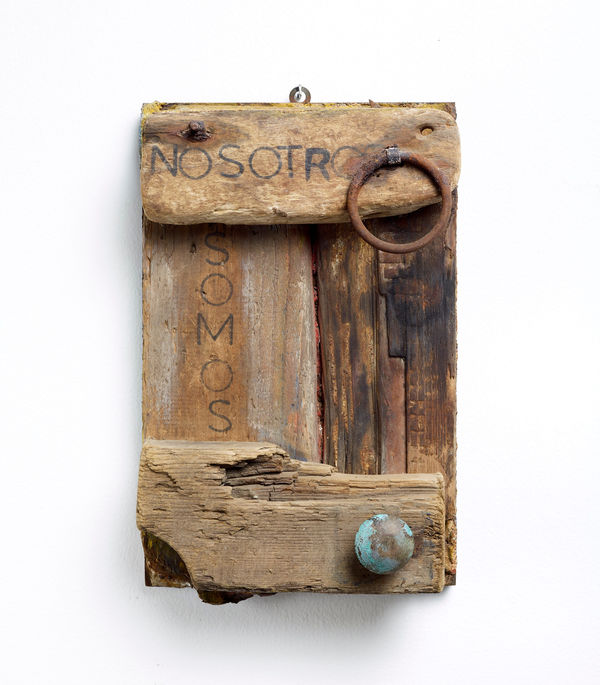

In Gramcko’s series of mixed media works from 1964, doors suggest the coexistence of two spaces: the one that the door encloses and the one that remains invisible. They also function as a metaphysical parable for the very content of the works, where they suggest an opening to the exterior world, while also retaining an enigmatic and protective quality in their closure.

Gramcko was interested in the symbolic as well as the ritualistic meaning of things, such as amulets and the cross as a universal symbol within and without Christianity. Her series of three-dimensional collages in medium and small-size formats were composed through conglomerate techniques, appropriating discarded metal parts and everyday objects such as marbles. Many of these works were specially made for her friends, as magical portraits.

-

-

Gramcko’s preferred mode of artistic expression was the three-dimensional, a drive we can trace in her early paintings. Nonetheless, she devoted only a few years of her practice to creating sculptures, which garnered her the National Award in Sculpture in 1968. The three small and medium-sized sculptures made of painted iron (1969) present quasi-totemic structures blended with industrial shapes. The black paint added to the metal creates a strong graphic component that flattens the works in space and a sense of elegant linearity.

-

-

Gramcko stated that her aim during the early 1970s was to immerse herself in the cultural roots of Latin America through the study of its archaic civilizations. Using ceramics and casein plastic, the artist made a modern version of bas-reliefs, reinforcing her three-dimensional impulse, and projecting what would be her replacement for a non-funereal nineteenth-century academic sculpture. Gramcko decontextualized a non-Western ritual object by isolating it as an icon.

The flat color backgrounds of Tikihao and Totem Nº 2 (1973 and 1974)—both purple and red—bring the works back to her first experiments in abstraction with chromatic hues that exacerbate the spiritual quality of the figures. El Arquetipo de Héroe, 1975 is a groundbreaking and rare totemic work that summarizes Gramcko’s archaic imaginary; composed of an earthy chromatic palette provided by a metal sheet and wood with mixed material.

-

“Gramcko’s neo-primitivist yearnings contained a critique of her own moment: her totems read as massive drill bits—toothy, with thick threads meant to twist into and out of the ground—as much as they do of revered quasi-human beings. Especially when rendered in two dimensions, using metal and acrylic paint mixed with organic materials, their surfaces scumbled and incised with marks that approach (but do not reach) the legibility of glyphs and—thanks to a color palette heavy in bony yellows and oxidized reds and rusty oranges—seemingly decayed, they begin to read like relics. These are not relics of the past, though—they are, in essence, relics of our present, what we will have left for the future.” - Aruna D’Souza

-

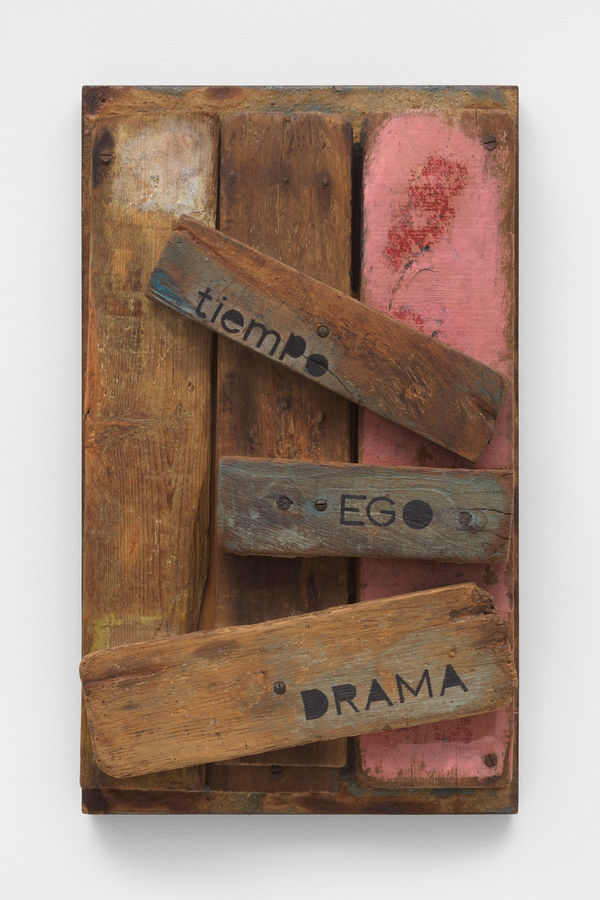

In her final series, known as Bocetos de un artesano de nuestro tiempo (Sketches by an Artisan of Our Time), Gramcko successfully overcame the inherent flatness of surfaces. It consists of wooden assemblages, to which she collaged elements of industrial debris and later marked with her own texts. These assemblages on wood began as compositions inspired by Piet Mondrian’s orthogonal structures with colored boards organized by the grid, such as the work Identificación plástica con un centro interior (Plastic Identification with an Internal Center), 1975.

-

-

Checklist

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1954

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1954 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1954

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1954 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1957

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1957 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, No. 6, 1957

ELSA GRAMCKO, No. 6, 1957

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1957

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1957 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-39, 1960

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-39, 1960 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1961

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1961 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-37, En el allá disparado desde ningún comienzo (R-37, There Within, Launched From No Beginning), 1960

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-37, En el allá disparado desde ningún comienzo (R-37, There Within, Launched From No Beginning), 1960

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-33, Todo comienza aquí (R-33, It All Begins Here), 1960

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-33, Todo comienza aquí (R-33, It All Begins Here), 1960 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, El león verde que devora al sol (The Green Lion Who Devours the Sun), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, El león verde que devora al sol (The Green Lion Who Devours the Sun), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Rueda de luz (Wheel of Light), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Rueda de luz (Wheel of Light), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Mundo que no ha nacido (World Not Yet Born), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Mundo que no ha nacido (World Not Yet Born), 1966

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Certera lumbre (Precise Brightness), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Certera lumbre (Precise Brightness), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Plenitud (Plenitude), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Plenitud (Plenitude), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Paracelso (Paracelsus), 1969

ELSA GRAMCKO, Paracelso (Paracelsus), 1969 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Intima Libertad (Intimate Freedom), 1965

ELSA GRAMCKO, Intima Libertad (Intimate Freedom), 1965

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Experiencia de luz (Experience of Light), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Experiencia de luz (Experience of Light), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-49, 1960

ELSA GRAMCKO, R-49, 1960 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1962

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1962 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título - Chatarra (Untitled – Metal Scrap), 1962

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título - Chatarra (Untitled – Metal Scrap), 1962

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1962

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1962 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, El castillo de Elsinor (Elsinore’s Castle), 1963

ELSA GRAMCKO, El castillo de Elsinor (Elsinore’s Castle), 1963 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Construcción con celdillas número 1 (Construction with Cells Number 1), 1963

ELSA GRAMCKO, Construcción con celdillas número 1 (Construction with Cells Number 1), 1963 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Una pequeña edad (A Small Age), 1964

ELSA GRAMCKO, Una pequeña edad (A Small Age), 1964

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, El castillo de los cerrojos (The Castle of Locks), 1964

ELSA GRAMCKO, El castillo de los cerrojos (The Castle of Locks), 1964 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Memoria (Remembrance), 1964

ELSA GRAMCKO, Memoria (Remembrance), 1964 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1965

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1965 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1965

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1965

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Cruz (Cross), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Cruz (Cross), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Comportamiento ante lo real (Behavior Before the Real), 1966

ELSA GRAMCKO, Comportamiento ante lo real (Behavior Before the Real), 1966 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1969

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1969 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título, (Untitled), 1969

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título, (Untitled), 1969

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1969

ELSA GRAMCKO, Sin título (Untitled), 1969 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Tikihao, 1973

ELSA GRAMCKO, Tikihao, 1973 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Totem Nº 2, 1974

ELSA GRAMCKO, Totem Nº 2, 1974 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, El arquetipo del héroe (The Hero’s Archetype), 1975

ELSA GRAMCKO, El arquetipo del héroe (The Hero’s Archetype), 1975

-

ELSA GRAMCKO, Identificación plástica con un centro interior (Plastic Identifications with an Intimate Center), 1975

ELSA GRAMCKO, Identificación plástica con un centro interior (Plastic Identifications with an Intimate Center), 1975 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Nº 5, de la serie bocetos para expresar nuestro tiempo (Nº 5, from the Series of Sketches to Express Our Time), 1976

ELSA GRAMCKO, Nº 5, de la serie bocetos para expresar nuestro tiempo (Nº 5, from the Series of Sketches to Express Our Time), 1976 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Tiempo, ego, drama (Time, Ego, Drama), 1976

ELSA GRAMCKO, Tiempo, ego, drama (Time, Ego, Drama), 1976 -

ELSA GRAMCKO, Motivación interior alrededor de un objeto (Inner Motivation Around an Object), 1977

ELSA GRAMCKO, Motivación interior alrededor de un objeto (Inner Motivation Around an Object), 1977

-

-

-

REFERENCES:

Elsa Gramcko’s letter to Alejandro Otero, 1961. Unpaged.Translation for Sicardi Ayers Bacino and James Cohan Gallery by Camilo Roldán.

Juan Calzadilla’s interview to Elsa Gramcko, 1976. Question no.14.

Gabriela Rangel, Curatorial Essay, Elsa Gramcko: The Invisible Plot of Things, 2022.

Katzenstein, Inés, María A. García, Karen Grimson, and Lacaze M. De. Sur Moderno: Journeys of Abstraction: the Patricia Phelps De Cisneros Gift., 2019. Print.

Ledezma, Juan, Cecilia Fajardo, Ella Fontanals-Cisneros. The Sites of Latin American Abstraction: Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection., 2008. Print.

Rangel Gabriela, Aruna D’Souza. Elsa Gramcko: The Invisible Plot of Things. Published by Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino, James Cohan, printed by Faenza Group, Italy, 2022, p. 89.

Ramírez, Mari C, Melina Kervanjian, Heather Brand, Anthony Beckwith, Héctor Olea, Tahía Rivero, María C. Gaztambide, Josefina M. Cabrera, and Gabriela Rangel. Contesting Modernity: Informalism in Venezuela, 1955-1975., 2018. Print.

Sánchez, Carlos. Hacia Elsa Gramcko, 35.

Schon, Elizabeth. Elsa Gramcko. In: Elsa Gramcko, Una alquimista de nuestro tiempo, Ediciones Galería de Arte Nacional, Caracas, 1997.

Individual images by Paul Hester and Phoebe d’Heurle. Installation images by Phoebe d’Heurle.

Special thanks to the team at Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino, Houston, Texas, Luis Felipe Farías, and Gabriela Rangel.

Elsa Gramcko: The Invisible Plot of Things: GALLERY EXHIBITION AT 48 WALKER ST | JANUARY 6 - FEBRUARY 15, 2023

Past viewing_room